At a group meeting in Paris on Thursday 4th November 1943 Gurdjieff was asked about communism.

L: Mr Gurdjieff, before I came to the work, I was very much concerned with political and social issues. And when I first heard the chapter on Ashiata Shiemash, it was extremely interesting to me, in that I could understand it. And almost instinctively I saw that this was all I could wish for. But there was one thing I couldn’t get away from. It is that of all the solutions that men propose today, there is one that I thought for the moment desirable. Not definite or perfect, but desirable: the communist solution. And since I’ve been working, I’ve been trying to rid myself of this belief. And little by little I understand what it is to see one’s nullity. A whole part of me wants to be rid of it that I can’t really get rid of it.

GURDJIEFF: What do you want to get rid of?

L: The belief that the communist solution might be desirable for the immediate future rather than the others… The efforts I have made so far have only partially detached me from it. My head is detached from it, but there is somewhere inside me where it remains, and I sense from certain reactions that I am not detached from it.

GURDJIEFF: I’ll talk politics with you for a while. I know about communism. I was a communist too. (my emphasis) There is no education in communism, there is no authority; they don’t recognize any, there must not be any. Everybody must be equal. If you have seen that in your own life it is impossible, you will understand that there too it is impossible. If you understand this, the communist idea can die in you. It must die if you know anything about Ashiata Shiemash. Communism is such that the instructors, the leaders are chosen from among the laymen, idiots who do not know anything at all; only people full of self-love and vanity are chosen. The system of Ashiata Shiemash is the opposite of all this. By comparison, other systems are nothing; whether it is communism or monarchism, it is equal. Only a fool full of defects will be chosen. You understand what I am saying and why I am saying it. One is a great idiot and the other a great idiot. They’re both the same shit. A collective existence can exist only with one method: that of Mr. Ashiata Shiemash.

Transcripts of Gurdjieff’s Wartime Meetings 1941-46 Book Studio 2024, pages 150, 151

What evidence is there to support Gurdjieff’s claim that he had been a communist?

Earlier in 1933, Gurdjieff had written;

I had in accordance with the peculiar conditions of my life, the possibility of gaining access to the so-called “holy-of-holies” of nearly all hermetic organizations such as religious, philosophical, occult, political and mystic societies, congregations, parties, unions etc., which were inaccessible to the ordinary man, and of discussing and exchanging views with innumerable people who, in comparison with others, are real authorities. (my emphases)

Gurdjieff, The Herald of the Coming Good, page 17

The revolutionary political party Gurdjieff’s name has been linked to was the early Social Democratic Party of Georgia, originally the Georgian branch of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party and later the Georgian Menshevik Party (after the split of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party into the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions at the Second Congress in Brussels in August 1903). Following the Russian Revolution the party became a vehicle for Georgian nationalism.

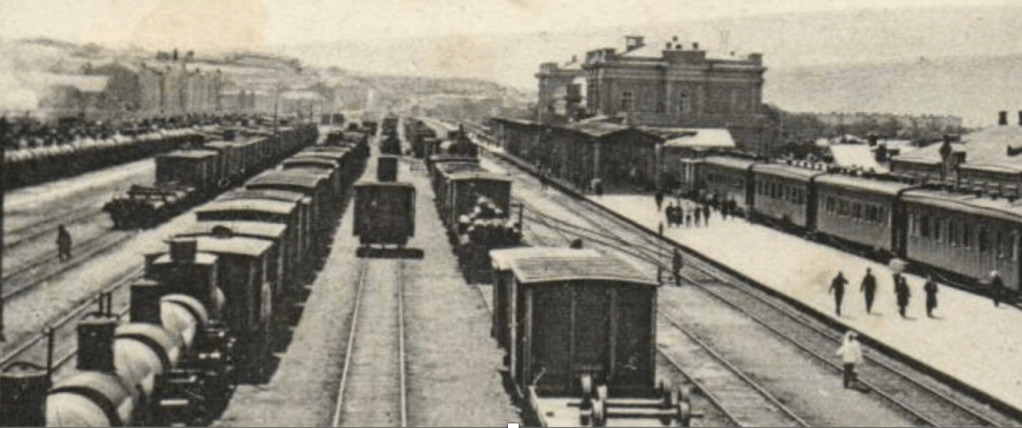

1894 Mesame Dasi railway workers’ study groups, Tiflis

Tiflis Railway Station

Gurdjieff was working as a stoker at the Tiflis Railway Station before being hired as a guide and translator for the party surveying the route for the new railway line from Tiflis (Tbilisi) to Alexandropol (Gyumri) in the spring of 1894.

https://www.academia.edu/129644525/ (Section 4c)

The Tiflis railway station, yards and works were the hub of the Transcaucasian railway system. As traffic, at that time (including oil traffic from Baku) had expanded, permanent locomotive and car shops (engine sheds, heavy repair shops, machine shops, smithies, carpentry, and stores) were built in Tiflis to perform heavy overhauls and rebuilds that smaller depots could not handle. The workshops employed a large skilled and semi-skilled labour force of approximately 3000 workers drawn from the city and surrounding region.

As such they were a focus of revolutionary activity and worker education, in particular by the Mesame Dasi, or Third Group, an illegal Marxist Social Democratic group founded in Tiflis in 1893. Two early members of this group, connected with the railway workshops, who Gurdjieff was later linked to, were Mikha Bochorishvili (1873-1913) and Silibistro Jibladze (1859-1922).

Mikha Bochorishvili, aka Mikhail Zakharevich Bochoridze

Mikha Bochorishvili

(photograph from Lavrenty Beria, On the History of Bolshevik Organizations in Transcaucasia, 1939)

Bochorishvili came from a working-class background. From 1890, when he was seventeen, to 1900 he worked as a blacksmith in the railway workshops gaining deep familiarity with the railway workforce. Starting in 1901, he transitioned to a bookkeeping role, which allowed him continued access to the railway environment while supporting administrative functions. He had joined the Mesame Dasi workers’ Social-Democratic circle in 1893 and became a leading figure in study groups at the railway depots, conducting propaganda sessions. These efforts focused on educating and radicalising railway workers against the tsarist autocracy.

Between 1897-1903 he served as a member of the Tiflis Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), using the workshops as a base for recruitment. He was active in Tiflis’s underground networks, where he mentored and collaborated with other revolutionaries. Notably, Joseph Stalin (then known as Iosif Dzhugashvili) later recalled receiving his “first lessons in practical work” in Bochorishvili’s presence during meetings in the home of comrade Sturua. These gatherings included figures like Lado Ketskhoveli (Djibladze), Sylvester Jikia (Chkheidze), and others, focusing on propaganda, worker agitation, and anti-tsarist organising among railway workers and factory labourers in Tiflis. He helped establish Bolshevik cells in Transcaucasia, distributing illegal literature.

In 1900 he played a prominent role in a major strike of approximately 4,000 railway shop and depot workers in Tiflis, coordinated with Stalin and others, marking a shift from small-scale propaganda to mass political action, including May Day demonstrations. He eventually joined the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), aligning with the Bolshevik wing led by Vladimir Lenin.

In 1903 he was elected to the Caucasus United (Bolshevik and Menshevik) Committee of the RSDLP and tasked with setting up a printing house and managing its work. Later he was part of the All-Caucasian Committee, directing Bolshevik efforts against Menshevik rivals. During the 1905 Revolution, which saw widespread strikes and uprisings in the Caucasus, he led armed worker detachments and strikes rooted in the railway sector. Arrested in 1906, he escaped and continued underground work across Transcaucasia and beyond.

Silibistro Jibladze

Jibladze, one of the organizers of workers’ strikes in Georgia, was actively involved in the formation of workers’ circles in railway workshops and various factories. He practically became the leader of Mesame Dasi in Georgia, worked for its organizational formation, and in 1898 even formed the Tbilisi Social-Democratic Committee, of which he was the chairman…

Sibistro Jibladze

After the defeat of the revolution of 1905, by the decision of the party, he was assigned to lead the implementation of terrorist acts. (my emphasis) In January 1906, Arsena Georgiashvili, directed by Jibladze, killed the Deputy Crown Prince of the Caucasus, General Fyodor Griaznov. Jibladze also organized the liquidation of several Bolsheviks. He collaborated in the following newspapers: “Beam”, “Gantiyadi”, and “Elva”.

Photograph and text

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silibistro_Jibladze

1903 Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in Switzerland

Writing about events at the end of 1904 Gurdjieff says

Secondly, as a result of the memory in my automatic mentation of the sight of all sorts of terrors flowing from the violent events which I had witnessed, and finally from accumulated impressions arising from conversations with various revolutionaries in the previous several years, first in Italy and then in Switzerland, and still more recently in Transcaucasia, (my emphasis) there had crystallized in me little by little, besides the previous unique aim, another also unconquerable aim. This other newly arisen aim of my inner world was summed up in this: that I must discover, at all costs, some manner or means for destroying in people the predilection for suggestibility which causes them to fall easily under the influence of “mass hypnosis.”

Gurdjieff, Life if Real, Only Then, When ‘I Am’. Page 27

To my knowledge, this is the only reference Gurdjieff makes to having been in Switzerland. One committed Marxist living in Switzerland prior to 1904, was his cousin, Sergei Dmitrievich Merkurov (1881-1952), later to become a famed Soviet sculptor. I believe one of the reasons Gurdjieff went to Switzerland in 1903, was to visit Merkurov.

Sergei Merkurov (1901) after graduating from the Tiflis Real School

Merkurov left Alexandropol in 1896 to attend the Nakhichevan Arts and Craft College, and continued on to the Tiflis (Tbilisi) real school from which he graduated in 1901. He then became a student at the Kyiv Polytechnic, and participated in political protests over workers’ strikes and demonstrations. In 1902 he was caught by the Cossacks, severely beaten in police custody, and expelled from the Polytechnic. Afterwards, he returned to Alexandropol, where he attempted to explain Marxism, capitalism, and socialism to his father, a first guild merchant.

My son, tell your old father what your teachers taught you? And what is this strange attire you are wearing?

Your uncle wears medals around his neck like a donkey with bells, so that from afar it can be seen and heard as he walks and proclaims: “The Tsar has honoured him.” I see gold insignia on your shoulders. You say these are our student uniforms: the Tsar’s name. Has this made you any wiser?

When we were young, a mullah at the madrassa told us, “Education is like polishing a stone: it reveals the stone’s inner qualities. If a stone is healthy, polishing makes it glow with health, beauty, and strength; if a stone has a crack, polishing makes the crack even more visible. If you’re a natural fool, education makes you not smart, but a polished fool. Intelligence is a gift of nature.”

Tell me, what has education added to your intelligence, which I naturally bestowed upon you as my son? What have the professors taught you? Tell me briefly, in a few words—you know, like in the Church of the Faith—so that I, a simple mountaineer, can understand you: short and simple, and speak honestly—after all, you are my son.

There was another student before you, he spoke at length. I’ll quote some of his words. Just give me a brief answer. He said: There is no God. Is that true?

– Yes, it’s true, father.

– A monkey gave birth to a man.

– Yes, it’s true, father.

– And that the rich stole their wealth from the poor.

– Yes, father, and it is true.

– Wait, wait, I even remembered his learned language: “Property is theft.” See what things I remembered.

– Yes, father.

– So it turns out that everything I have, I stole from someone.

– It turns out so, father.

“And it was I who spent the money, the professors polished your brains, so that in them, as in a mirror, I would see my image in old age – the image of a thief. Well, thank you for that.”

In the morning, the worker handed me a small basket with two pairs of underwear, a ticket to Tiflis station, and 4 rubles 50 kopecks change from 10 rubles, saying:

“The master asked me to tell you that an honest man has no business in a thief’s house. He is my son, flesh of my flesh, bone of my bones—he will understand.”

Early in the morning, without saying goodbye to anyone, I left my parents’ house. Heading to the train station. I passed an ancient church. The menacing angels were illuminated by the slanting rays of the sun. They seemed even more defined, even more expressive. Dark and winged, he threatened me with a sword from above, and the soul of a sinner trembled in his hand.

I had already walked far from the church, but an angel threatened me with a sword from afar. The sword glowed in the sun’s rays—the angel held a blaze of fire in his hands and cast me out.

And I left.

Gone forever.

A CONVERSATION WITH MY FATHER ABOUT GOD AND PROPERTY (Alexandropol, 1902) from his memoirs written in 1932

Photograph and text from Archive G.S. MERKUROVA

Published from the manuscript in the book: “S.D. Merkurov. Memories. Letters. Articles. Notes. Opinions of Contemporaries.” Moscow, Kremlin Multimedia, 2012 (in Russian)

Mercurov’s rejection of his father and his values contrasts with Gurdjieff’s deep respect for his father and gratitude for his seemingly harsh methods in preparing him for life in a challenging world. Some ten years later Gurdjieff was to observe the following about the naivete of his cousin;

Among my acquaintances here in Moscow there is a companion of my early childhood, a famous sculptor. When visiting him I noticed in his library a number of books on Hindu philosophy and occultism. In the course of conversation I found that he was seriously interested in these matters. Seeing how helpless he was in making any independent examination of these related questions, and not wishing to show my own acquaintance with them, I asked a man who had often talked with me on these subjects, a certain P. (Vladimir Pohl-my insert) to interest himself in this sculptor. One day P. told me that the sculptor’s interest in these questions was clearly speculative, that his essence was not touched by them and that he saw little use in these discussions. (my emphases)

Glimpses of Truth, Views from the Real World, Early Talks of Gurdjieff, Page 53

In the autumn of 1902 Merkurov had gone to Switzerland to study in the faculty of Philosophy, at the University of Zurich. At the time Switzerland was one of the cheapest places to live in Europe. He attended lectures by Lenin in Zurich and later became close friends with him.

At the start of the 20th century, Geneva and particularly Rue de Carouge, was a nest of Russian revolutionaries and exiles. Around 2300 Russian students, mostly female medical students, were attending Swiss universities, making up the vast majority of the foreign student contingent. They coexisted with a sizable community of political refugees. One of them recalled:

“Geneva was literally swarming with Russians, and Russian was heard everywhere, in cafes, in restaurants, and in the streets.”

Specifically, the Carouge-Bastions-Jonction triangle represented and housed all political forces opposing the tzarist authority. While the Bolsheviks dominated Rue de Carouge (named “Karoujka” by Russian students), Rue Caroline was the stronghold of the enemy brothers Mensheviks (i.e., the minorities, more prone to debate) and Anarchists (i.e., who were for the hard way and bombs).

Visiting his cousin in Switzerland, Gurdjieff would have found Geneva, with all its Russians, an ideal place to have had “conversations with various revolutionaries.” Lenin and his wife had moved there from London in April 1903.

Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924)

They moved then to Rue de Carouge 91 and 93, where they stayed between May and June 1903 in a house which still exists and whose facades remain still the same as they were in 1903, Lenin occupied the two apartments on the ground level. The structure literally served as the Bolsheviks’ European headquarters, housing the party’s archives and library (around 4000 books and 120 journals).

The Lepenchinsky canteen was also housed in that structure, where all revolutionaries could always find cheap food and drinks and discuss over six large tables and a piano. ……

In addition to the Lenin group (Vatslav Vorovsky, Nikolai Semachko, Anatoly Lounacharski, Grigori Sokolnikov, Grigori Zinoviev, Nikolai Bukharin), one may encounter Menshevik leader Julius Martov and, on rare occasions, Leon Trotsky, who spent the fall of 1903 in Geneva.

Stefano Meroli, Lenin and Geneva: the story of an unknown love

https://scienceshot.com/post/lenin-and-geneva-the-story-of-an-unknown-love

1904 The Gurian Republic

Gurdjieff says he was again in Georgia at the end of 1904. He claims to have been shot by a stray bullet near Chaitura, during fighting between the Gurians and the Cossacks. As to why he was there he says

my propensity during this period for always traveling and trying to place myself wherever in the process of the mutual existence of people there proceeded sharp energetic events, such as civil war, revolutions, etc.,

Gurdjieff Life if Real, Only Then, When ‘I Am’. Page 27

The Gurian Republic was an insurgent community that existed between 1902 and 1906 in the western Georgian region of Guria (known at the time as the Ozurget Uyezd) in the Russian Empire. It rose from a revolt over land grazing rights in 1902. Several issues over the previous decades affecting the peasant population including taxation, land ownership and economic factors also factored into the start of the insurrection. The revolt gained further traction through the efforts of Georgian Social Democrats, despite some reservations within their party over supporting a peasant movement, and grew further during the 1905 Russian Revolution.

(One of the Menshevik Georgian Social Democrats who helped the peasants in their armed revolt in 1905 was Silibistro Jibladze.)

During its existence, the Gurian Republic ignored Russian authority and established its own system of government, which consisted of assemblies of villagers meeting and discussing issues. A unique form of justice, where trial attendees voted on sentences, was introduced. While the movement broke from imperial administration, it was not anti-Russian, desiring to remain within the Empire.

The 1905 Russian Revolution led to massive uprisings throughout the Empire, including Georgia, and in reaction the Russian imperial authorities deployed military forces to end the rebellions, including in Guria. The organised peasants were able to fend off a small force o Cossacks, but the imperial authorities returned with overwhelming military force to re-assert control in 1906.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gurian_Republic

The conditions in the Caucasus at this time are vividly described by the Italian writer, traveller and later diplomat Luigi Villari (1876-1959) in his book recording his observations and conversations with leading figures from all communities during his travels through the area in the summer and autumn of 1905. Regarding the situation in the Gurian Republic he writes.

The policy of the Russian Government has alternated between concessions and coercion. While it sent a liberal university professor from St. Petersburg to study the Narodny Sud, and the method of communistic administration, it inaugurated a series of exekutzii, i.e., it quartered troops in villages at the expense of the villagers, and sent detachments of Cossacks and infantry to reduce the people to order. Desperate fighting has taken place in and around Ozurgety. The railway has been cut again and again, and several military trains have been derailed with heavy loss of life, and every day troops along the line have been attacked. When the troops have been successful, they have shot down the Gurians without mercy, and the whole province is drenched in blood.

Luigi Villari, Fire and Sword in The Caucasus, London 1906, page 99

https://archive.org/details/cu31924028756082/mode/2up

Villari also reported that labour unrest had evolved from strikes to armed actions and assassinations.

Having been helped to flee wounded to Ashkhabad in Russian Turkestan, Gurdjieff recounts

I am barely moving through the narrow streets, and come across only small ashkhanas, where only Tekinians sit. I am weakening more and more, and in my thoughts already flashes a suspicion that I may lose consciousness. I sit down on the terrace in front of the first chaikhana I pass, and ask for some green tea. While drinking tea, I come to—thank God! -and look around on the space dimly lit by the street lantern. I see a tall man with a long beard, in European clothing, pass by the chaikhana. His face seems familiar. I stare at him while he, already coming near, also looking at me very intently, passes on. Proceeding further, he turns around several times and looks again at me. I take a risk and call after him in Armenian: “Either I know you, or you know me!” He stops, and looking at me, suddenly exclaims, “Ah! Black Devil!” and walks back. It was enough for me to hear his voice, and already I knew who he was. He was no other than my distant relative, the former police court interpreter….. on the following morning this distant relative of mine, the former police official, came to me accompanied by his friend, a police lieutenant….there were now many dangerous revolutionaries everywhere…. and secondly, added my distant relative, lowering his voice, your name appears on the list of sources disturbing for the peace of visitors to “Montmartre,” places of frivolous amusement. (my emphases)

Gurdjieff Life if Real, Only Then, When ‘I Am’. Pages 14-16

To avoid arrest Gurdjieff says he travelled further east “to the city of Yangihissar in Chinese Turkestan” (Yengisar, Xinjiang).

What was Gurdjieff doing in Chiatura that resulted in tsarist authorities throughout the Caucasus and Russian Turkestan seeking his arrest? It is odd that he claimed there was military actions between the Gurians and Cossacks near Chiatura which is not in Guria but Imereti. Georgian historian Manana Khomeriki has highlighted the geographical inconsistences in Gurdjieff’s account. I believe his presence in the area was more likely related to the 1904 Chiatura Manganese Mine Strikes.

The manganese deposit in Chiatura, in the Imereti region of western Georgia, is one of the largest in the world. In 1904 its mines supplied nearly 60% of the world’s manganese ore. The mines were owned mainly by foreign companies. Most miners were Georgian peasants working under gruelling conditions: 18-hour shifts, sleeping in mine shafts, constant exposure to toxic dust, and no basic amenities like washing facilities. They employed around 3,700–4,000 miners.

The miners were striking over nonpayment or delay of wages, inhumane working hours, impossibly high ore-production quotas, lack of safety and medical care and terrible housing and food. Attempts were made to coordinate with railway workers (so ore transport could be disrupted). Armed miner detachments (combined Bolshevik and Menshevik) had been established to enforce control, protect sympathetic mine owners, and resist the tsarist forces. In 1905 a Menshevik member of these squads was (Valerian) Bilanov (Bilanishvili) (1869-1938) who was later linked to Gurdjieff in police files.

1903-1906 The Avlabari illegal printing house, Tiflis

The Avlabari underground printing press is now a modern tourist attraction in Tbilisi, named The Stalin Underground Printing House Museum (AKA Stalin’s Printing Press or the Museum of Avlabari).

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/stalins-underground-printing-house

For the full Stalin fan story see

Ekaterina Mikaridze, Secrets of the declassified Avlabari underground printing house, SPUTNIK Georgia 21/07/2023

(In Russian)

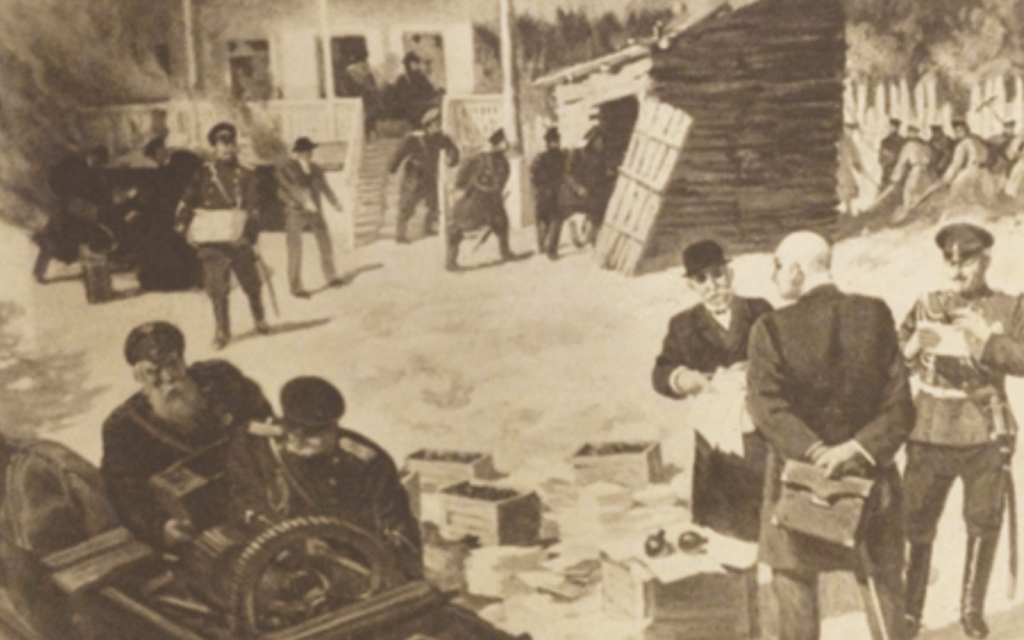

Avlabari Printing House (reconstruction of 1937)

However, this is not the original establishment which was destroyed by tsarist authorities in 1906, but a reconstruction built in 1937 at the height of the great terror. It was part of Lavrenty Beria’s campaign to flatter Stalin. This included publishing a book, On the History of Bolshevik Organizations in Transcaucasia, that rewrote Boshevik history, making false claims and exaggerations about Stalin’s involvement in many of the events. For details of the controversies surrounding the book and how the material was collected, and how those who didn’t agree with the account were later arrested and shot, see

(no author given) Little Stories. Almost namesakes…

https://little-histories.org/2014/12/05/beria_book/?ysclid=mh2sp4af4w291637521

(In Russian)

The full story of the rebuilding of the underground printing works and the house above as a museum, glorifying Stalin’s exploits, is covered by

Irakli Khvadaglani, Light from the Underground – Avlabari’s Illegal Printing House, The Laboratory for the Research of the Soviet Past, 6/12/ 2011

(In Georgian)

In reality Stalin had nothing to do with the printing house. He was in jail and later in exile during its existence.

To make their ideas known, the revolutionaries circumvented the censorship of the tsarist authorities by establishing illegal printing presses. Everything started as a makeshift printing house, with wooden typefaces or by spending the night in closed official printing houses. Over time, a class of professional typesetters and conspiratorial distributors already armed with stolen typeface, moved from rented apartment to rented apartment or took refuge in the most unlikely places.

The gendarmerie quickly traced and shut down the early printing presses in Tiflis. So, in 1903 Mikha Bochorishvili was tasked on behalf of the Caucasian Union Committee of the Russian Social Democrat Labour Party with organising and operating a new secret printing house. He approached a close comrade Davit Rostomashvili, (1871-1944) who had previously worked with him at the railway workshops as a locksmith. Rostomashvili was also known as a poet and folklorist who had been publishing poems since the 1890’s, writing under the pseudonym D. Ninotsmindeli. The pair asked Rostomashvili’s father to let them use part of a plot of land he leased in Avlabari.

At that time, this area was on the outskirts of the city, and rarely frequented. A garden was already on the site where the house was to be built. Rostomashvili submitted a fictitious building plan to the city council. A house was then built on the plot, beneath which was an underground basement intended for the printing works. It could only be accessed by descending a well inside a shed, then through a horizontal tunnel to a second well, and climbing up a staircase inside that well to reach the printing workshop.

During construction, the workers were replaced twice, to cover their tracks and enhance secrecy. The first group, who dug the underground basement that was to be used for the printing works, were dismissed citing bankruptcy of the owner. The second group, well diggers, were dismissed after they had only dug nine metres. The work was completed by the revolutionaries and took six months to finish.

For security, Mikha’s aunt, Babe Lashadsze-Bochoridze, lived in the house. She cooked for the workers and kept a constant watch on the street. If strangers approached the house, the workers were warned by a secret bell to stop working, so that the sound of the printing press didn’t give them away.

Sketch of the underground printing works

The location of the printing house was kept strictly secret, even the leaders of the Social Democratic Party did not know its location.

It was heavily utilized, churning out up to 45,000 copies daily -organisational documents of the RSDLP, works by Lenin, leaflets, appeals, the newspapers “Proletariatis” (The Struggle of the Proleteriat and “Proleteriatis Brdzolis Purtesli “(The Leaflet of the Struggle of the Proleteriat) and others.

Eventually the gendarmerie established that there was a large printing works somewhere in Tiflis. It was said at the time that its discovery took considerable time and effort, but by the beginning of 1906 they already had an approximate idea of its location.

In 1906, the Tsar’s Okhrana intensified surveillance of the building and 0n April 13, 1906, Bochorishvili clearly noticed the spies, so the house was immediately vacated and a sign left: “House for Rent.”

On April 15, 1906, the house was searched as part of a mass search, and the printing works found by chance. A gendarme officer threw a sheet of burning paper into the well to test its depth, and the horizontal tunnel near the bottom of the well leading to the printing works sucked the paper inside. The officer realised that there was something under the building.

On April 18 of the same year, the Minister of Internal Affairs wrote: “We have seized a large printing house and an explosive shell workshop in Tbilisi, which belonged to the Social-Democratic and Military Organizations…”

Ivane Vepkhvadze (1888-1971) painting, The raid on the illegal printing house in Avlabari by the gendarmerie, 1937

The printing press equipment, typefaces, paper stocks, and all unfinished materials (including revolutionary pamphlets) were seized and removed. The house above ground was razed to prevent further use. The well and tunnel entrance were filled with soil to seal off access to the underground space, effectively burying the chamber.

1906 Giorgi Gurdjieff, “specialist” in the manufacturing of explosive devices

In early 1906 the Union Committee had established a joint military group to manufacture explosives and study street fighting with barricades. It consisted of three from the Bolshevik faction (Mikha Bochoridze, Nushik Zavariani, and Nina Alajova) and three from the Menshevik faction (Silibistro Jibladze, Kalistrate Gogua and Kotsia Chachava). In January, Jibladze had orchestrated the assassination of the Deputy Crown Prince of the Caucasus, General Fyodor Griaznov.

Georgian historian, Professor Tengiz Simashvili presented his archival research on Gurdjieff’s involvement with this group on his Blogger.com blog in November 2016. George Gurdjieff in Georgia (1906) (in Georgian). Recently (September 2025) he has added updated Russian and English translations.

In brief (edited)

In his memoirs Davit Rostomashvili (published under the pseudonym “D. Ninotsmindeli” in The Chronicle of the Revolution, no. 4, 1923) says that at the beginning of April 1906, Mikha Bochorishvili asked him for “empty rooms above the printing press… because one of the best teachers has come, he is unemployed, and we want to learn how to prepare explosive material”. Rostomashvili wanted to know who the teacher was and the next day, in the morning, he came to the house, where he met Mikha Bochorishvili, Kotsia Chachava, and two young women, whom he said he did not know at that time.

Later the “teacher” arrived – “a man of medium height, very dark skinned, with a face that glistened as if oiled.” Two young women meet him at the gate… The teacher met them very cheerfully. He spoke to me in Armenian. The women did not respond to every word, from which I concluded they did not know the Cilician Armenian language… I began to suspect the teacher and involuntarily said: “Khachagogha” (swindler, liar according to the slang of this period). Rostomashvili confided his suspicion to Bochorishvili’s aunt, who was offended: “Mikha is experienced in this matter and would not make such a mistake.” A few days later, Mikha Bochorishvili told him that spies had surrounded the press and that things were going badly. Soon after, the printing press was indeed discovered, and arrests followed.

In the memoir published in The Chronicle of the Revolution, no. 2(12), 1925, under the title “From the Distant Past” and authored by Nina Alajova and Nushik Zavarian — the “two young women” previously unnamed by Rostomashvili — we read:

“In mid-January 1906, the Tbilisi Committee of the Social-Democratic Workers’ Party appointed a group composed of several comrades to study the methods of partisan struggle (street fighting with barricades, etc.), as well as the manufacture of explosive devices (grenades, mines, etc.)…

“To study this matter, we invited a ‘specialist-engineer’ (a Greek), who, according to comrade Jibladze, had rendered great service to our organization in Mikhailovo, when the Tsarist Cossacks suppressed the revolutionary uprising there.”

In The Chronicle of the Revolution, no. 1(16), 1927, Davit Rostomashvili once again published a memoir which, while similar to his 1923 account, differs in several details.

Here he again mentions Gurdjieff multiple times and retells his meeting with the “teacher” from a slightly different perspective. He notes that when Gurdjieff arrived late, he began conversing with the young women, whom he now identifies by name — Alajova and Zavarian. According to him, the teacher spoke to them in the Cilician Armenian dialect and “was of medium height, dark-eyed and dark-browed, his face shone like tanned leather, he resembled a Negro from afar, dressed elegantly in European fashion, constantly smiling while speaking with the women… To me, the teacher seemed like some Don Juan.”

In this second memoir, Rostomashvili recounts his prison conversation with Nikolaz Sikharulidze:

“In prison Kolia Sikharulidze was brought in. He asked me why the printing press had been betrayed, and when he heard Gurdjieff’s name, this is what he told me: “In Khashuri, that Gurdjieff swindled us out of three thousand rubles, promising to teach us how to make explosives. We studied with him for several weeks, and finally asked him to demonstrate. We went out into the field and threw one [grenade] — it didn’t explode. Then a second, a third… The comrades became furious with Gurdjieff. One of them even tried to beat him up. After that we never saw Gurdjieff again.”

Gurdjieff’s connection with Nikolaz Sikharulidze was confirmed by Professor Simashvili from police records.

On January 26, 1906, the head of the Gori branch of the Transcaucasian Railway Gendarmerie Police Department sent the following letter to the head of the Tiflis Gubernia Gendarmerie Department: “In addition to the telegram I sent on January 14 of this year, I inform you that in the town of Mikhailovo the manufacture of explosive grenades has been detected, in which are implicated: student George Gurdjieff, agent of the Singer Company Nikolai Sikharulidze, and student Vladimir Bilanov. The first two may have fled to Guria, while the third is living somewhere in Tiflis.”

https://tengizisimashvili.blogspot.com/2025/09/george-gurdjieff-in-georgia-1906.html

That the “teacher” was Gurdjieff is confirmed by the descriptions of him being “very dark skinned” and that “he resembled a Negro from afar”. At the end of the opening chapter of his book Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, Gurdjieff describes himself as being known as He who in childhood was called “Tatakh”(Armenian ritualistic soaking of bread in red wine); in early youth “Darky”; later the “Black Greek”… Furthermore, his distant relative in Ashkhabad had addressed him as “Black Devil”.